Introduction

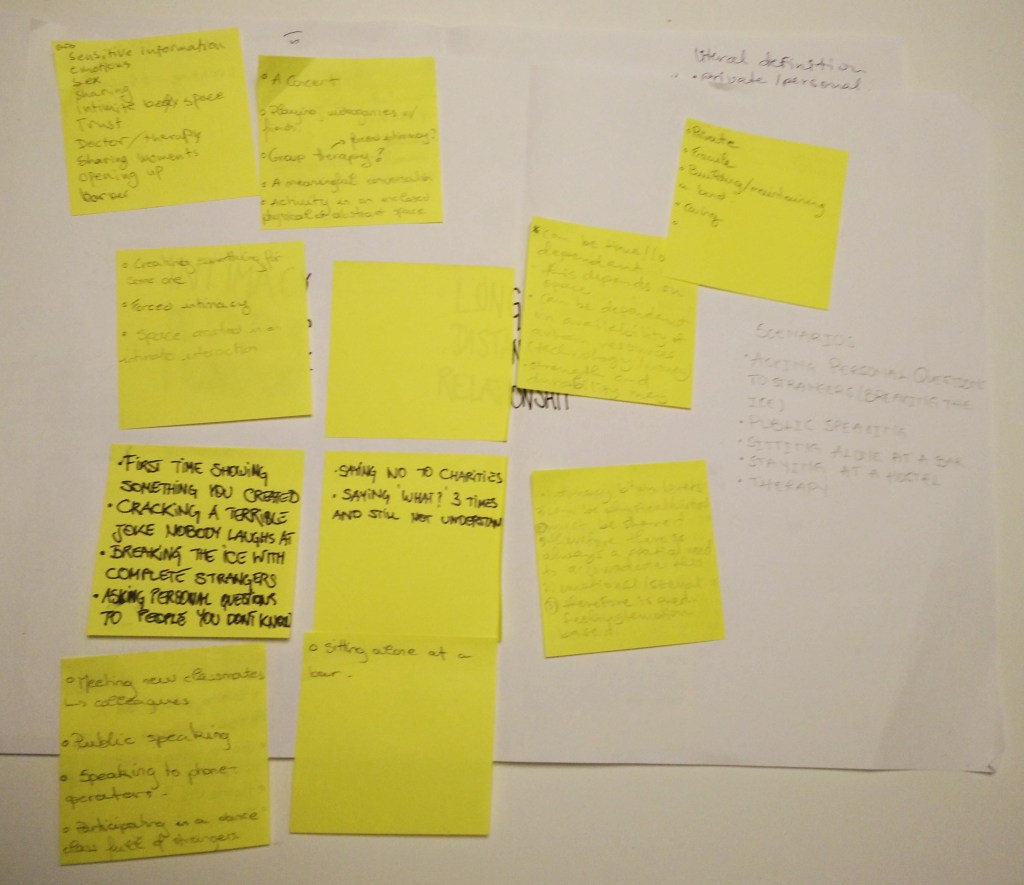

In this essay, I will argue that it is problematic to use nuances as a driving factor to develop and iterate an interactive artifact. The base of argumentation will be my personal experience with working with interactivity and fabrication of artifacts along with methods and approaches rooted in the course literature. By nuances as a driving factor it is meant that the nuanced input the user makes and why it is problematic to be used as a basis for design iteration.

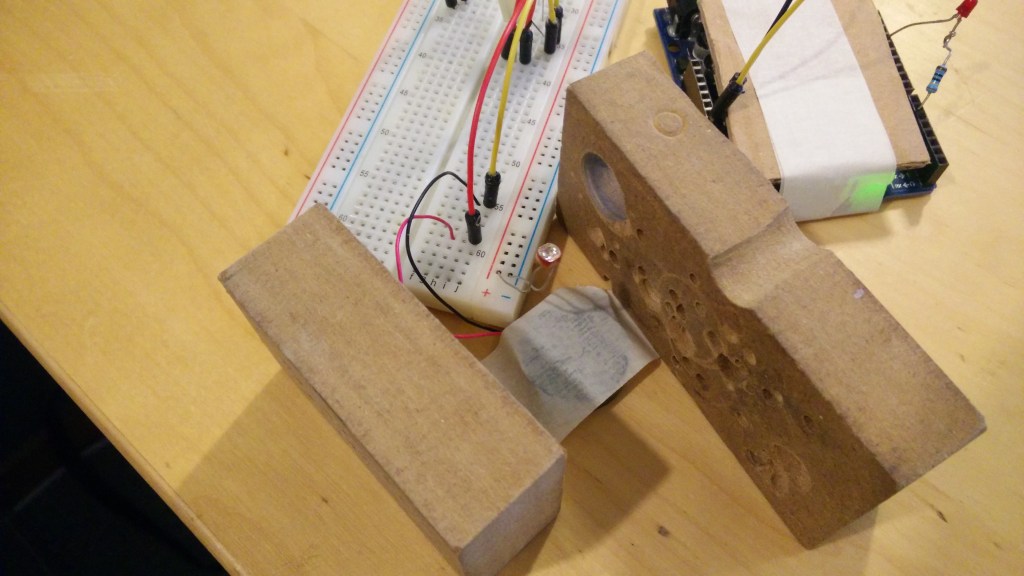

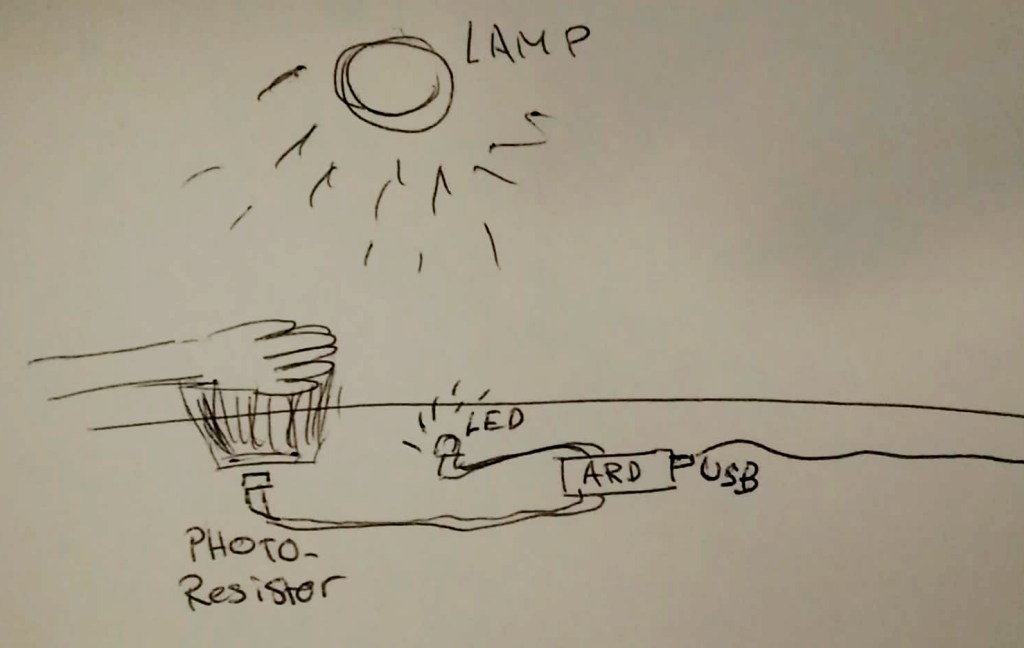

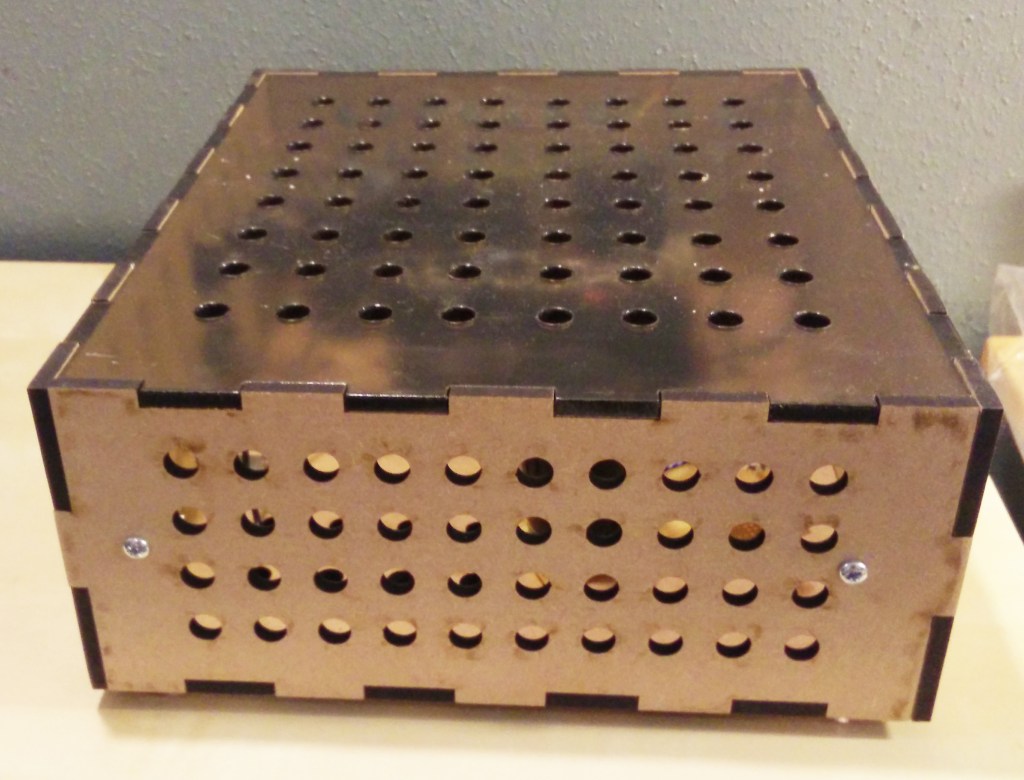

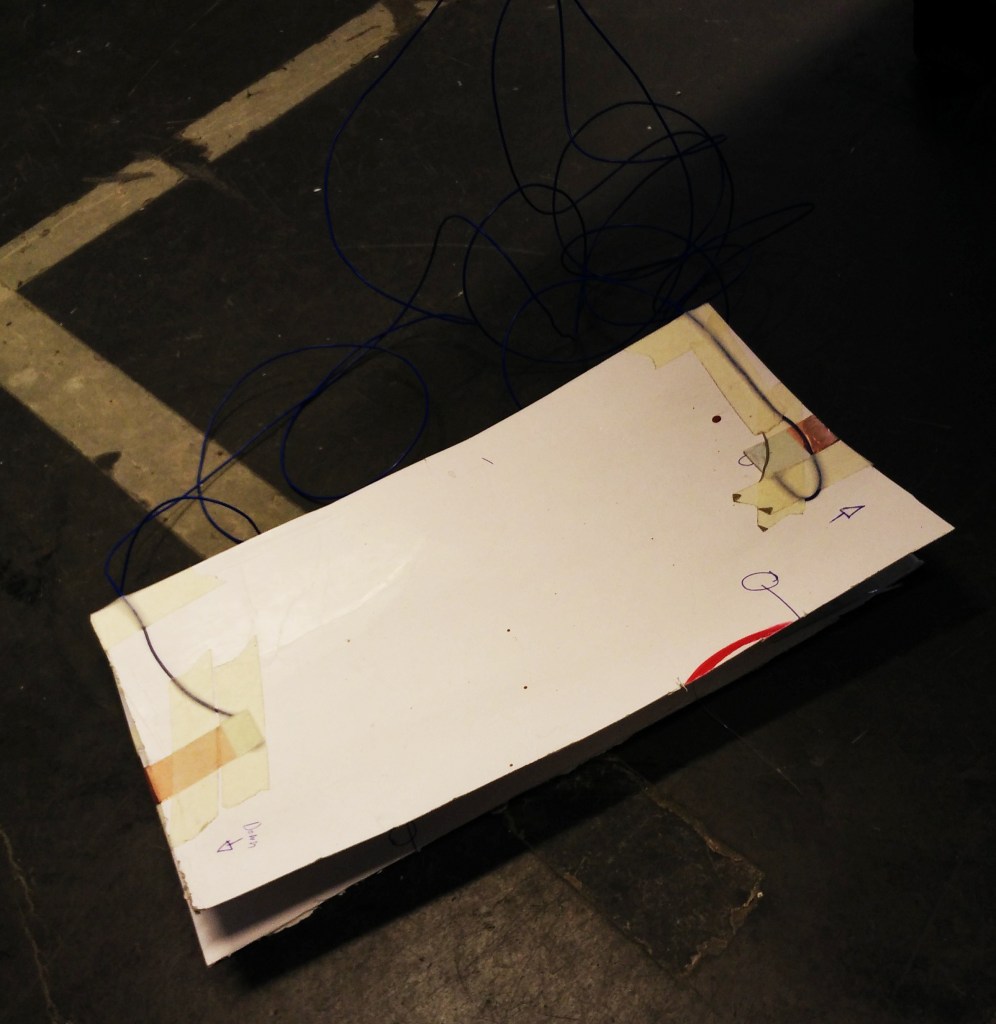

With nuanced input of an artifact, it is described as a term on how to make an artifact with a multitude of varying inputs a user can make when interacting with it. Nuance from a physical and bodily expression is any way, shape, or form a user can possibly think of when interacting with an object given the interaction is within the sensory boundaries of the artifact. The object possesses various sensors that act as inputs in which the human input can be translated into a language that the artifact can understand. The medium for transportation and interpretation of human input interaction has been, during this course, a computer and a microcontroller. Sensors used to capture sound and motion were a basic microphone, web camera, and a proximity sensor. Three different fields within interactivity were probed and with each field, an artifact was made. A nuanced way of interacting with the artifact was one of the goals with the object.

The quality and intrinsic limitations of sensors

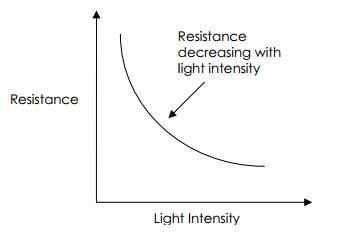

Fogtmann, Fritsch & Kortbek (2008) relates sensors as the sense organs of the computer. It is explained that there are a lot of different types of sensors that can capture human interaction. Common sensors such as camera, microphone, and proximity sensors are ubiquitous today, they can be found everywhere and most of them are already integrated into the host device. For my design work, I did use the built-in camera and microphone from the laptop. The proximity sensor for the microcontroller was a common budget model. It is worth pointing out that the quality of the sensors and the resolution they can record at, can’t be ignored. I would argue that the mere fact that there is a different quality to choose a sensor from is further complicating the design process when trying to apply a nuanced input from a design approach.

Nuance from our perspective can imply different things to people, depending on the environment, the setting, and the user. Movement pattern and our capacity to learn over time influenced by social and cultural context develops our understanding of when and how to put in a specific effort (Fogtmann et al, 2008). A painter might apply different techniques and a varying amount of nuanced brushstrokes in order to create the painting. Speed, pressure, and movement are nuances that are highly responsible for the outcome in this example. If there isn’t a direct coupling between the input interaction and the displayed result the artifact exhibits, the loop comes to an end. Resulting in a negative interaction experience with the artifact.

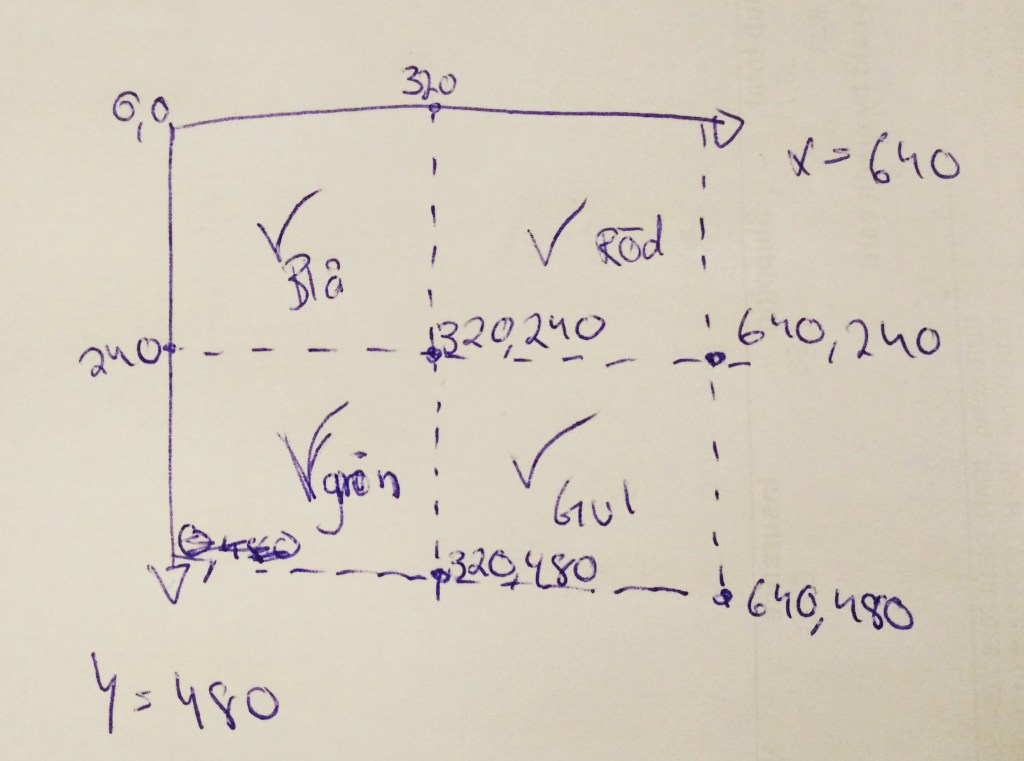

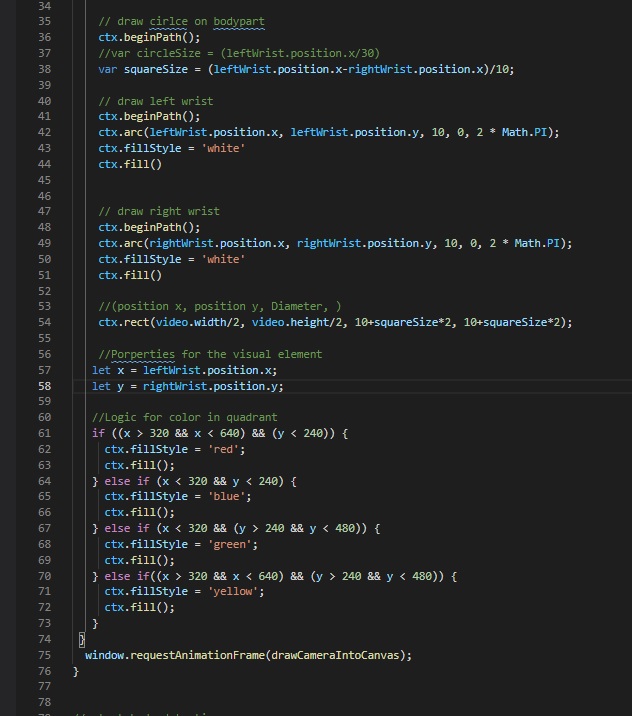

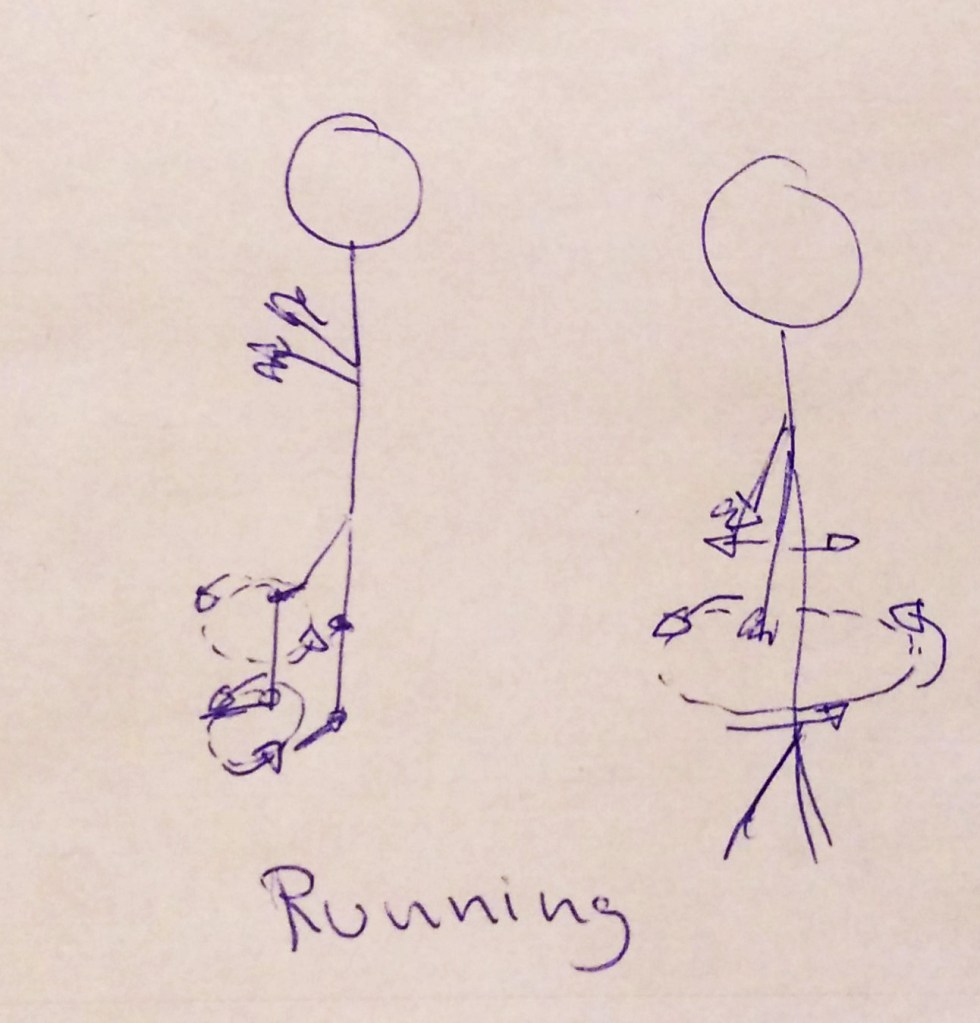

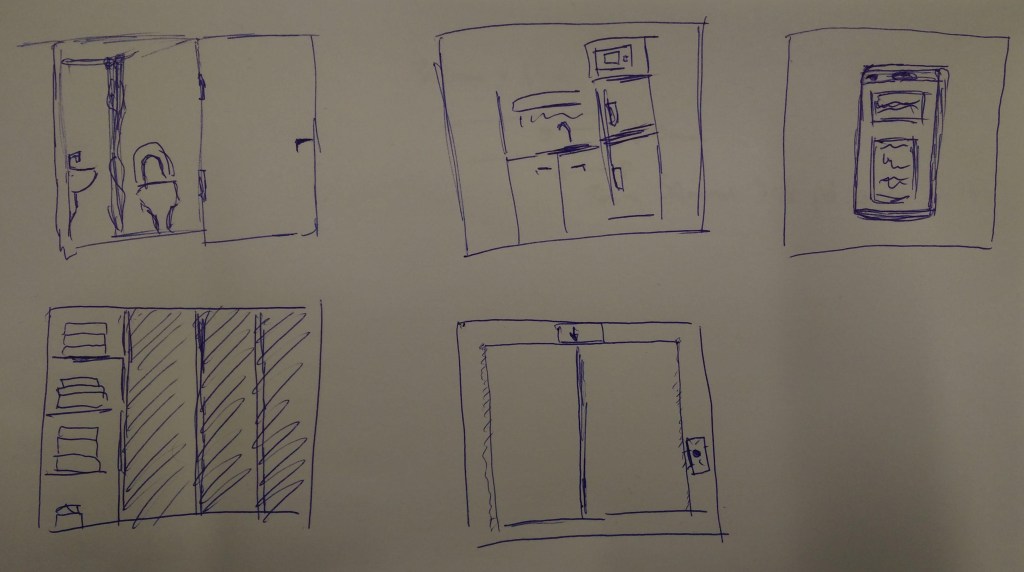

This was the issue with the artifact produced in module three during the course. A built in webcam from a laptop was used to track the motion of a user. Multiple tracking points were programmed into the software to follow. The user can approach this artifact with the view that there is a possibility to use the body in a nuanced way.

While the user is contained within a three dimensional space, the camera does not have to take that into account. The only technical input requirement it needs is a body to track and record that is within its specific framework. Using a high resolution camera which can record a higher rate of megapixels would be able to capture more accurate nuanced bodily movements but it would require more processing power from the computer and it’s not certain it would succeed in capturing with hundred percent accuracy. This points to the argument that the quality of the sensors can improve the accuracy of which the sensor can record at but only to a certain point, before it either hits an intrinsic limitation or the system needs too much processing power that it is not a viable approach to design with from the first start.

Nuance in the physical world contra digital artifacts

Djajadiningrat, Matthews & Stienstra (2007) mention skill and expression as a method to interact in a nuanced manner with physical objects around us to enrich the interactive user values. Usability as a user value is brought up as a problematic area that is in strict relation with how well a user can interact with an artifact, hence poor usability will in most cases result in a negative user interaction.

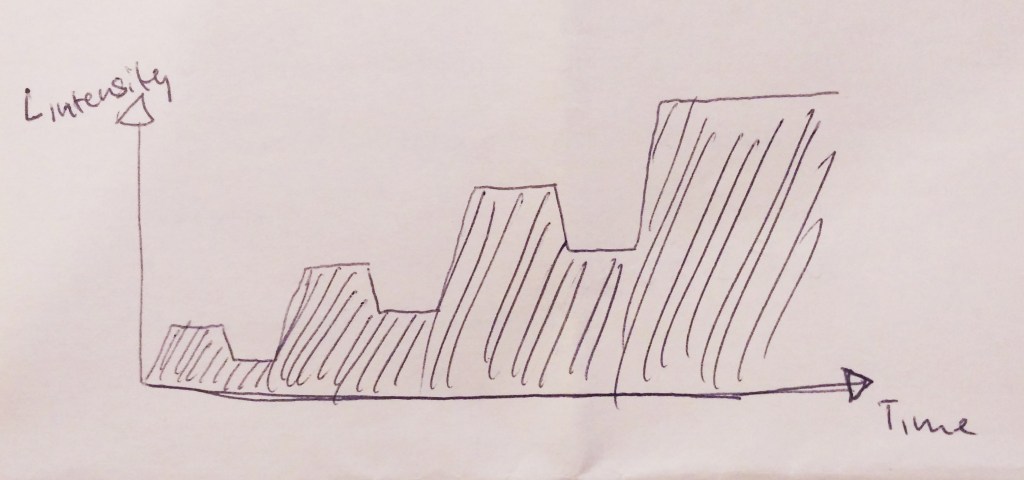

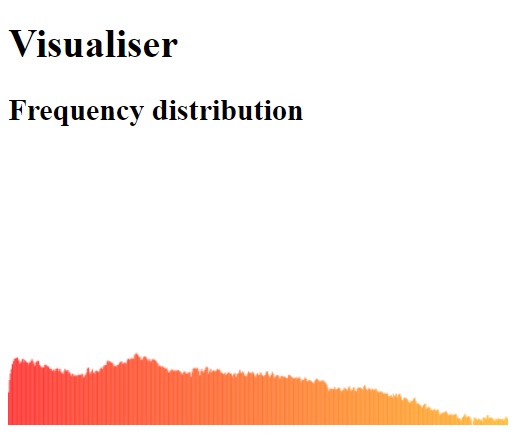

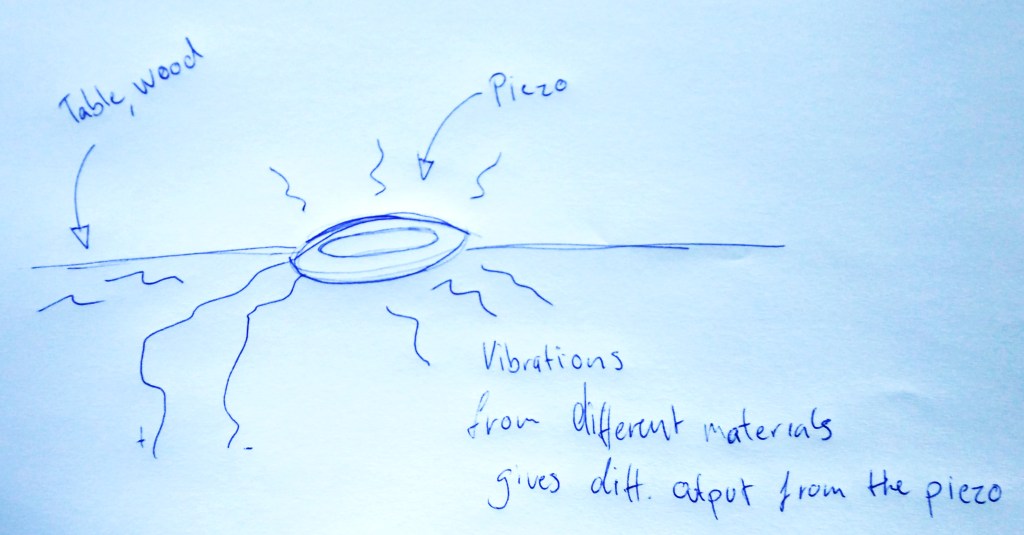

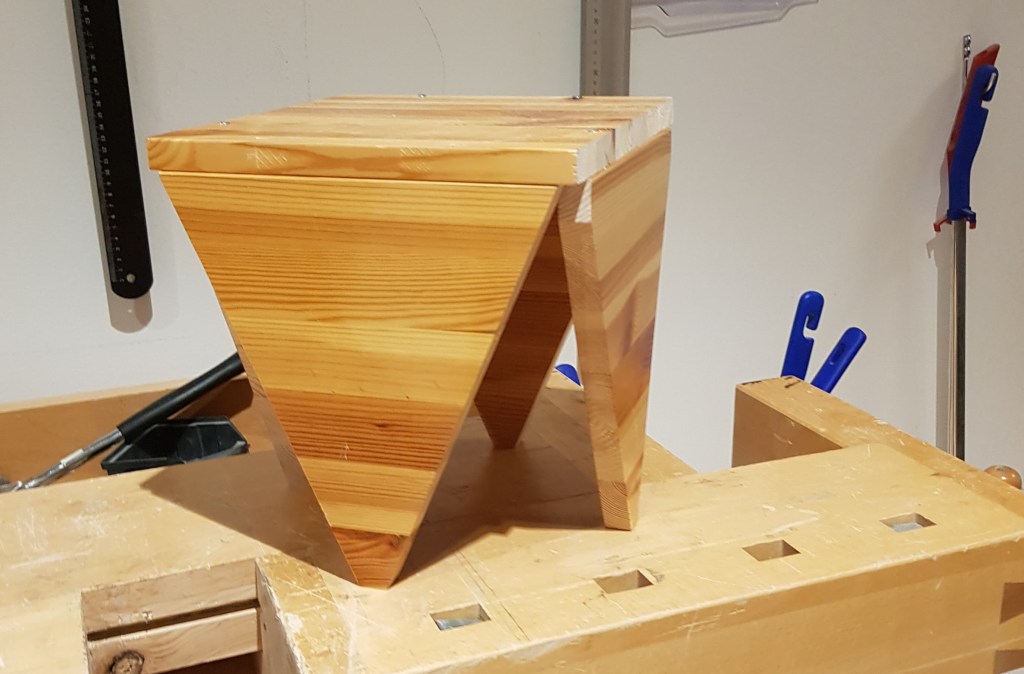

The result of the first interactivity module was an artifact where the user inputs a bodily skill to produce sound. The sound sample was then picked up by the microphone of the laptop and translated into a numerical value and used to control and display a specific color on the screen. The user could choose the right lightness, hue and color by producing a sound within a frequency, threshold, and peak. The way that the user can input this sound is highly nuanced. The motion, force, and material that produces the sound can be combined into many possibilities. The caveat of designing such a highly nuanced requirement for the input is that the digital world can’t interpret the skill as we do in the physical world.

We are surrounded by boundaries and physical laws that dictate our possibilities to interact. These rules are very complex and not necessarily applicable in the digital world. Many rules don’t apply in the digital environment that the artifact is situated in and the argument lies in that there is an overlap between the physical and digital world in which context isn’t really clear. For instance it doesn’t matter the amount of speed, motion or force that was applied to the input. The microphone doesn’t take into account what we try to achieve with these attributes and neither the context or setting. It only listens for the raw value in which everything is included, it’s own vibrations produced by the computer it is built in and the ambient noise. Nuanced interaction is complex and requires a holistic view of the situation and material in order to work, this holistic view is something that shines with its absence in the digital world. Not because it isn’t implemented but rather that it is impossible to make work in that world.

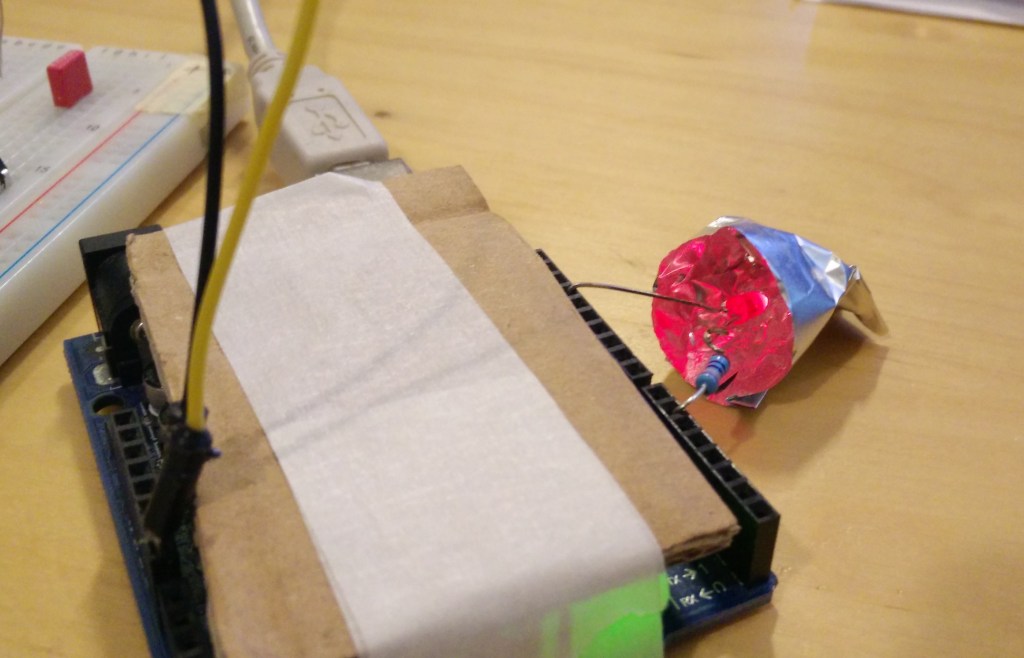

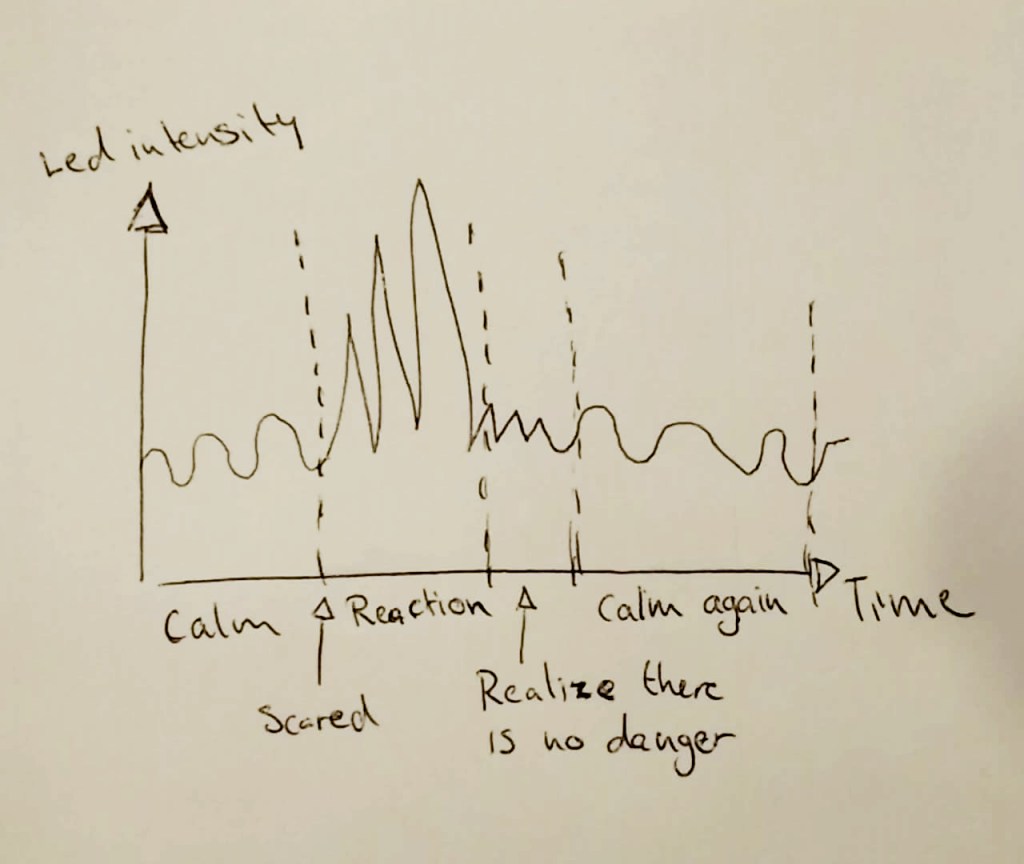

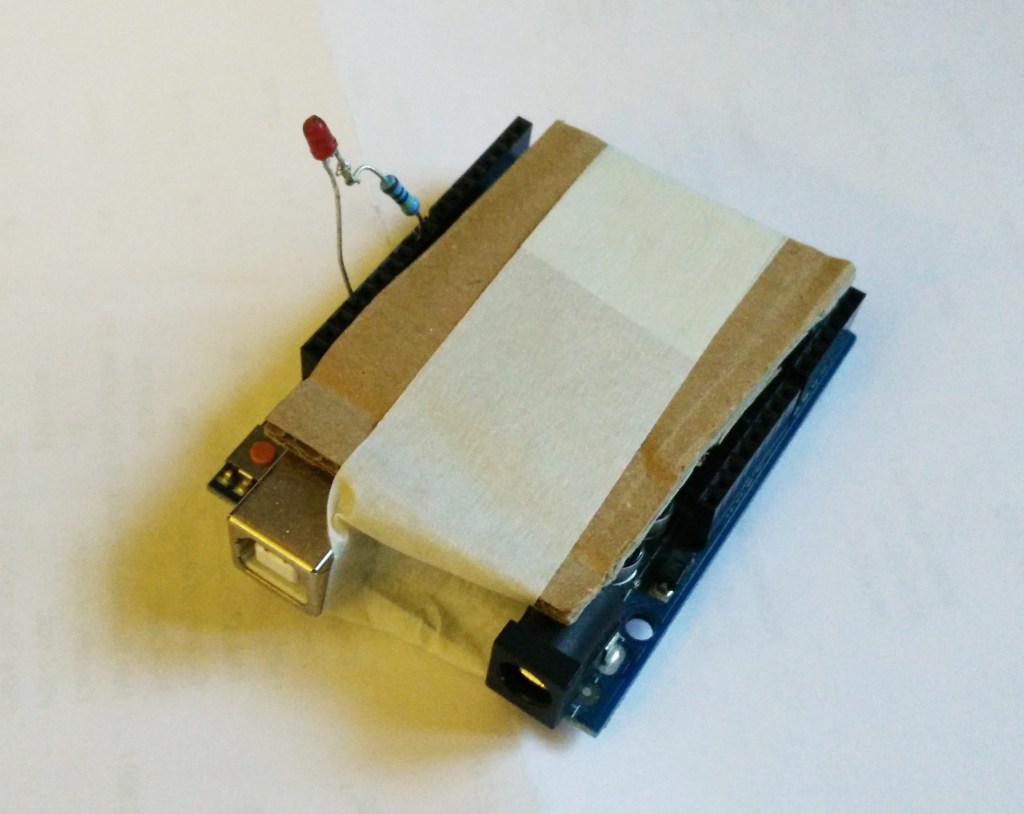

When we interact with each other we use our senses, experience, and understanding of the world to interpret something. Human emotion is something we tried to incorporate in module two. By giving an LED the ability to mimic a human emotion of being scared (by blinking rapidly) when it is approached too quickly or when a sudden sound is made. It is evident that no real human factors played any role when the led would blink. It simply is reacting when it’s told to by its own rules in its digital world set by the designer. What this argument highlights is the discrepancy between the real world where we have to account for different kinds of rules than just measuring distance and sound triggers.

Dreyfus (2002) mentions skill as something we continually develop and draw upon from our past and present experience of the real world. As a result, we are equipped with an understanding of what kind of response we can use in that context. Nuances on the input inherits therefore complex attributes as inclusiveness and sustainability which come naturally. By inclusiveness, it is meant that the action required at the input isn’t locked to a value represented by exact numbers. Variances in action should have the possibility to exhibit a consistent and reliable outcome. Human interaction is far from perfectly replicable and asking the user to repeat the same action in a perfect accurate manner would not only exclude users that can’t perform the designed action but would also introduce a question whether or not the artifact is interpreting the input correctly. Given the error margin in the sensors and the way we interpret our movements as being perfect when in reality it is not. It is argued that “Current interfaces indeed seem to be built on the assumption that interaction can be captured in schemata and that the body is merely a mechanical executor”(Djajadiningrat et al., 2007, p.659). A counter argument would be that it makes sense from an artifact perspective to receive input in a strictly monotone and non-nuanced way. The result of the interaction would yield a perfect match in input to output interaction.

Nuanced input and output coupling

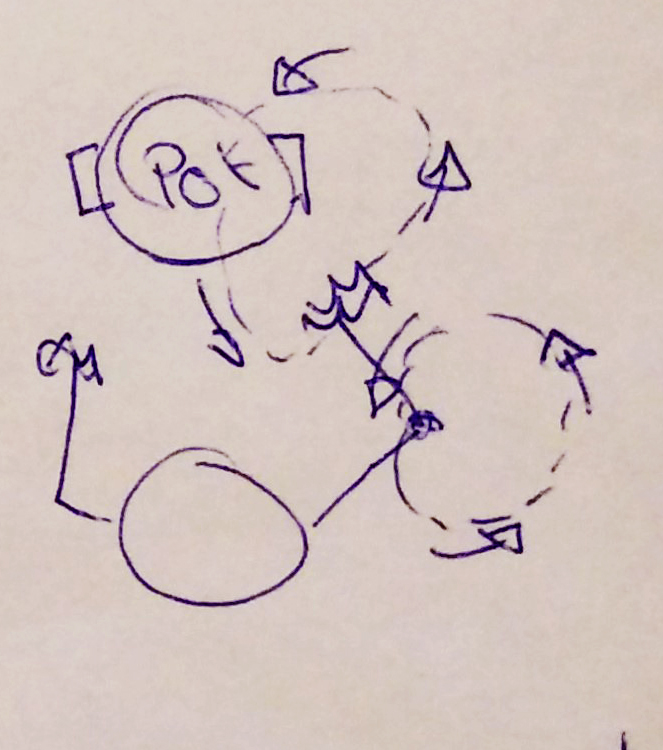

During the time period of the interactivity course, I have developed and used nuanced input as a driving factor to enhance the interaction of the artifact. In the first module, there was a clear issue with trying to fabricate an interaction with nuance as the main quality for input. The continuous approach of using nuance as a way to further iterate the artifact was problematic. A human-computer interaction where the user could use a variety of nuanced movements to generate sound for the input, materialized in a counter-intuitive and asperous interaction. Notably, the lack of coupling between the input responsiveness and accuracy in the output interaction was pointed out as the main culprit. “Physical user actions and product reactions should not be seen as separate. The coupling between action and reaction is quintessential to interaction and considering the coupling of physical actions and reactions opens up a new space for design aesthetics and movement-based interaction” (Djajadiningrat et al., 2007, p.658). The weak relation between the input and output coupling not only limits and breaks the interactive relation they share but it will also limit possible design aesthetics and movement-based interaction which are key qualities when crafting a nuanced input.

Conclusion

The quality and physical limitation of a sensor should be considered as guidelines on how well a nuanced interaction can be exhibited at the artifact. I argue that there is a gap between human nuances and the resolution of which the sensor can record. This inevitably will present issues in the experience but it is also leading the development of the artifact into the wrong path. Nuance as the key quality for input is a troublesome approach which results from engagement in artifact design has exhibited. An alternative approach of using nuance as a driver for developing an interaction would be to assess the limitation and quality of the sensors and material before starting the artifact development. Once the variables and behaviour of the sensor is known, a limited and reasonably nuanced input interaction can be designed.

One of the key arguments in this essay is the argument that there is a evident discrepancy between how nuances are viewed in the physical world we live in and the digital world. The argument encapsulates the main issue with using nuanced input as a driving factor in artifact development. The reason being evident after hands-on experience with designing artifacts and the reason is that the digital world can’t interpret nuanced skill as we do in the physical world. Physical laws command our possibility to interact and perceive, whereas the digital artifact follows a different set of rules. Nuanced input becomes a trivial input in the digital artifact world as all the context, emotion and nuance from the real world is discarded for the mere recording of raw data.

The expected relation between input and output from a digital artifact is often considered a usability question. The argument for coupling the nuanced input to an equally nuanced output is critical in succeeding with meaningful and sustainable interaction. The situation is bound to be unequal given the argument that nuanced input can’t be equally matched by nuanced output. Hence why my standpoint of using nuances as a factor to develop and iterate an interactive artifact is not recommended as an iterative approach.

References

Djajadiningrat, T., Matthews, B., & Stienstra, M. (2007). Easy doesn’t do it: skill and expression in tangible aesthetics. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 11(8), 657-676.

Dreyfus, H. L. (2002). Intelligence without representation—Merleau-Ponty’s critique of mental representation. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 1(4), 367–393.

Fogtmann, M. H., Fritsch, J., & Kortbek, K. J. (2008, December). Kinesthetic interaction: revealing the bodily potential in interaction design. In Proceedings of the 20th Australasian conference on computer-human interaction: designing for habitus and habitat (pp. 89-96).

You must be logged in to post a comment.